| Illuminations Home |

|

| St.

Louis Cardinals |

|

| Von der Ahe Years |

|

| Gashouse Baseball |

|

| St. Louis Swifties |

|

| Beginning

of the Busch Era |

|

| Gibby

& El Birdos |

|

| Whiteyball |

|

| Enter

the "Genius" |

|

| Baseball Heaven |

|

| Visiting Busch Stadium |

|

| Do the Cubs Really Suck? |

|

Illuminations, Epiphanies, & Reflections

Enter "The

Genius"

|

Just like

clockwork, the Cardinals began a long-term slump as they entered

the odd-decade of the 1990s. Following Herzog, a former Cardinal

star during the doldrum 1970s, Joe Torre, was given the opportunity to

lead the team. Unfortunately after a short resurgence in

1991, the team languished in mediocrity for the next four years.

In 1996,

Anheuser Busch sold the team to a

group of investors led by Bill O. DeWitt Jr., who--advised by General

Mangager, Walt Jocketty--lured Tony LaRussa

away from the Oakland Athletics to join the

Cardinals. Over his managing career with the Chicago White Sox

and the A's, LaRussa, who graduated with a law degree from Florida

State University in 1978, had earned a reputation for his intelligence

and mastery of tactical baseball. When he arrived in St. Louis,

LaRussa immediately started wheels turning with Jocketty to bring

several of his

favorite players from Oakland to play for the Cardinals.

Incredibly, LaRussa's team--including three A's veterans, Dennis

Eckersley, Rick Honeycutt, and Mike Gallego--captured the Central

Division title, however they weren't able to make it past the Atlanta

Braves in the Division Championship series. In 1996,

Anheuser Busch sold the team to a

group of investors led by Bill O. DeWitt Jr., who--advised by General

Mangager, Walt Jocketty--lured Tony LaRussa

away from the Oakland Athletics to join the

Cardinals. Over his managing career with the Chicago White Sox

and the A's, LaRussa, who graduated with a law degree from Florida

State University in 1978, had earned a reputation for his intelligence

and mastery of tactical baseball. When he arrived in St. Louis,

LaRussa immediately started wheels turning with Jocketty to bring

several of his

favorite players from Oakland to play for the Cardinals.

Incredibly, LaRussa's team--including three A's veterans, Dennis

Eckersley, Rick Honeycutt, and Mike Gallego--captured the Central

Division title, however they weren't able to make it past the Atlanta

Braves in the Division Championship series. The following year, LaRussa convinced Mark McGwire to join him in St. Louis at mid-season, and Big Mac started his prodigious three year assault on Busch  Stadium's

outfield seats. Already a famed power

hitter, in 1998, McGwire's home run tear, along with the Cubs' Sammy

Sosa, captivated the entire nation. Stadium's

outfield seats. Already a famed power

hitter, in 1998, McGwire's home run tear, along with the Cubs' Sammy

Sosa, captivated the entire nation. Toward the end of the 1998 season, a reporter noted the presence of Androstenedione in McGwires' open locker. At that time--although Andro had been banned by the Olympics, the NCAA, and the blind-eyed NFL--it was an over-the-counter, testosterone-producing, strength enhancer that was advertised on ESPN, sold in healthfood stores, and completely legal to use, not just in major league baseball but anywhere in the United States. However, the tabloid press, led by the New York Times, had a field day raising alarm about the "discovery." McGwire, seeming genuinely surprised and frustrated by the controversy, responded "It's

legal and nobody even bothered talking to our trainers," he said just

after hitting his 52nd home run of the year, "There's absolutely noting

wrong with taking it. . . . Everything I've done is

natural. Everybody that I know in the game of baseball uses the

same stuff."

Players lined up behind him, defending his right to use the capsules, and Baseball Commissioner Bud Selig endorsed McGwire's actions in a press release the several days later, "In

recent days there have been press reports concerning the use of certain

nutritional supplements by major league players. The substances

in question are available over the counter and are not regulated by the

Food and Drug Administration. In view of these facts, it seems

inappropriate that such reports should overshadow the

accomplishments of players such as Mark McGwire."

So, the home run race between McGwire and Sosa continued until the end of the season. When McGwire broke Roger Maris's record with his  62nd home run,

St. Louis and the rest of the country went wild, and when he hit his

69th and 70th home run of the year on the last

day of the season, it seemed like a feat that would never be equaled. 62nd home run,

St. Louis and the rest of the country went wild, and when he hit his

69th and 70th home run of the year on the last

day of the season, it seemed like a feat that would never be equaled.In the years that followed McGwire's home run record, the furor over Andro increased, and the drug, though technically a testosterone precursor and not a steroid, was classified as such and became obtainable only by prescription. Additionally it was banned from use in professional baseball. After San Francisco Giants slugger Barry Bonds was implicated by a grand jury for using illegal steroids as part of his training regimen, and Jose Conseco accused a number of ballplayers of using steriods, McGwire, Sosa, and others were called before Congress to testify on steroid use in major league baseball. While others  emphatically stated that they had never used steroids,

McGwire,

who had acknowledged his use of Andro back in 1998, simply stated that he did not wish to address the past

when he was

pressed whether he had used steroids or knew any ballplayers who

had. Strangely, nobody on the panel ever asked McGwire anything

about Andro and whether he considered it to be a steroid.

Regardless, by the time McGwire reached his first year of eligibility

for possible election to the Hall of Fame, both the popular press and

the baseball writers had become so "outraged" over steroids

that he didn't stand any chance of being selected to join that elite

group. emphatically stated that they had never used steroids,

McGwire,

who had acknowledged his use of Andro back in 1998, simply stated that he did not wish to address the past

when he was

pressed whether he had used steroids or knew any ballplayers who

had. Strangely, nobody on the panel ever asked McGwire anything

about Andro and whether he considered it to be a steroid.

Regardless, by the time McGwire reached his first year of eligibility

for possible election to the Hall of Fame, both the popular press and

the baseball writers had become so "outraged" over steroids

that he didn't stand any chance of being selected to join that elite

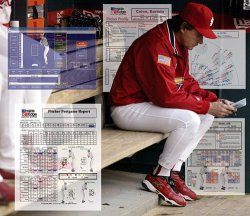

group. More to the point of this page, however, was that McGwire's three-year home run binge, effectively took the pressure to win off of LaRussa's shoulders. From 1997 to 1999, the Cardinals continued to field mediocre teams, and nobody noticed because of Big Mac. More importantly, those years gave LaRussa and Jockerty time to trade for key players, sign some free agents, and develop emerging youngsters.  By 2000, the team had come into it's own and over the next seven years it would win six Division Championships, two National League Pennants, and one World Series. In 2004, the Cardinal juggernaut went 105-57, capturing the Cardinals' first National League pennant since 1987, but it suffered an unexpected and disappointing four-game sweep at the hands of the Red Sox in Boston's year of destiny.  Despite his consistent success, LaRussa had

become an object of scorn

for a very vocal group of Cardinal fans who referred to him with

tongue-in-cheek derision as "the genius" for his unorthodox

on-the-field , statistically-based decisions, especially his continuous

pitching

changes. Many fans were disappointed that his teams were unable

to make it over the hump in the postseason and a sizeable minority

mistakenly believed that he compared unfavorably to Whitey

Herzog. Actually, LaRussa's record for his first eleven years as

the Cardinal manger is considerably better than Whitey's: 979-803 for a

.549 winning percentage vs. 894-826 for .520. It wasn't until

LaRussa, in one of his finest years ever as a manager, took the heavily

injured Cardinal team to the World Championship over the Detroit

Tigers in 2006 that he was really accepted by most of the Cardinal

Nation. Despite his consistent success, LaRussa had

become an object of scorn

for a very vocal group of Cardinal fans who referred to him with

tongue-in-cheek derision as "the genius" for his unorthodox

on-the-field , statistically-based decisions, especially his continuous

pitching

changes. Many fans were disappointed that his teams were unable

to make it over the hump in the postseason and a sizeable minority

mistakenly believed that he compared unfavorably to Whitey

Herzog. Actually, LaRussa's record for his first eleven years as

the Cardinal manger is considerably better than Whitey's: 979-803 for a

.549 winning percentage vs. 894-826 for .520. It wasn't until

LaRussa, in one of his finest years ever as a manager, took the heavily

injured Cardinal team to the World Championship over the Detroit

Tigers in 2006 that he was really accepted by most of the Cardinal

Nation.Following the 2005 season, old Busch Stadium was demolished and work on a new Busch Stadium home for the Cardinals was completed. The 2006 Cardinals got off to a hot start as Mark Mulder won the first game played in the new ballpark, 6-4 against the Milwaukee Brewers.  First Pitch at the New Busch Stadium

One week later Albert Pujols blasted three consecutive homers in a victory over the Cincinnati Reds. But injuries caught up with the Redbirds, sidelining David Eckstein,  Pujols, Mulder, and Edmonds.

During that time, the team lost eight games in a row in June, the first

time it had done so since 1988. After a semi-recovery, the still

unhealthy team was rocked with another eight game losing streak at the

end of July. Amazingly, the Cardinals remained in first place as

the rest of the division teams were having similar problems.

Despite additional injuries to star reliever Jason Isringhausen and

Scott Rolen, by mid-September, the Cardinals appeared to be on the road

to another 90+ win season and enjoyed a seven and a half game lead over

the second place Cincinnati Reds and an eight and a half game lead over

the third place Houston Astros. Incredibly, the Cardinals lost

another seven Pujols, Mulder, and Edmonds.

During that time, the team lost eight games in a row in June, the first

time it had done so since 1988. After a semi-recovery, the still

unhealthy team was rocked with another eight game losing streak at the

end of July. Amazingly, the Cardinals remained in first place as

the rest of the division teams were having similar problems.

Despite additional injuries to star reliever Jason Isringhausen and

Scott Rolen, by mid-September, the Cardinals appeared to be on the road

to another 90+ win season and enjoyed a seven and a half game lead over

the second place Cincinnati Reds and an eight and a half game lead over

the third place Houston Astros. Incredibly, the Cardinals lost

another seven games in a row, while the Astros won ran up a string

of

nine consecutive

victories. With a post-season visit on the line,

Scott Spiezio tripled in

the winning runs on the penultimate day of

the season and

secured the

Redbirds at least a tie for the Division

Championship. When the Astros lost the following day, a shaky

but nearly mended Cardinal team headed to San Diego to play the Padres

in

the first round of the playoffs. games in a row, while the Astros won ran up a string

of

nine consecutive

victories. With a post-season visit on the line,

Scott Spiezio tripled in

the winning runs on the penultimate day of

the season and

secured the

Redbirds at least a tie for the Division

Championship. When the Astros lost the following day, a shaky

but nearly mended Cardinal team headed to San Diego to play the Padres

in

the first round of the playoffs.As the playoffs began, no baseball writers picked the Cardinals to advance beyond the Padres, but if they were paying attention to the health of the team, they should have. As the year ended, several of the Cardinals had just about recovered from their long-standing injuries. Veteran Jim Edmonds stepped in as the unofficial captain of the team, and after the Redbirds beat the Padres in the first game, he established a post-season tradition of awarding gameballs, football-style, to deserving teammates. The Cardinals appeared refreshed and had gained a new lease on life. They took two of the next three games and advanced to the National League Championship Series against the heavily favored New York Mets. Once more, the Cardinals were prohibitive favorites to lose. In game one, Jeff Weaver, an apparently washed-up pitcher that Dave Duncan took on as a reclamation project, was called upon to start. Although he did well, the Cardinals lost 2-0 when their old nemesis, ex-Astro Carlos Beltran, launched a towering home run. The Mets took control of game two but the Cardinals  fought back to tie the score following New York leads of 3-0, 4-2, and 6-4. Then in the top of the ninth,

So

Taguchi, who had entered the game as a defensive substitution for Chris

Duncan the previous inning, led off. Taguchi had

joined the Cardinals in 2002 as a light-hitting outfielder from the

Orix BlueWave in Japan.

Although a superb defensive player, his hitting had improved

considerably in the four years since he arrived. To the dismay of

almost everyone in Shea Stadium, Taguchi blasted a line drive off of

Mets star reliever, Billy Wagner into the outfield seats, and the

Cardinals evened the

series at one game a piece, winning 9-6. fought back to tie the score following New York leads of 3-0, 4-2, and 6-4. Then in the top of the ninth,

So

Taguchi, who had entered the game as a defensive substitution for Chris

Duncan the previous inning, led off. Taguchi had

joined the Cardinals in 2002 as a light-hitting outfielder from the

Orix BlueWave in Japan.

Although a superb defensive player, his hitting had improved

considerably in the four years since he arrived. To the dismay of

almost everyone in Shea Stadium, Taguchi blasted a line drive off of

Mets star reliever, Billy Wagner into the outfield seats, and the

Cardinals evened the

series at one game a piece, winning 9-6. In Game 3, held in Busch Stadium, the Mets couldn't touch Jeff Suppan, the Cardinals' starter, although St. Louis easily handled  Mets

pitching. Even Suppan

homered, and the Cardinals took a 2-1 series lead, winning 5-0. The St. Louis bullpen fell apart

in Game 4, and the Cardinals lost 12-5 as the Mets evened up the series

at 2-2. Jeff Weaver started his second game of the series in Game

5, and after again giving up two early runs, shut down the Mets.

The Mets

pitching. Even Suppan

homered, and the Cardinals took a 2-1 series lead, winning 5-0. The St. Louis bullpen fell apart

in Game 4, and the Cardinals lost 12-5 as the Mets evened up the series

at 2-2. Jeff Weaver started his second game of the series in Game

5, and after again giving up two early runs, shut down the Mets.

The Cards recovered and won the game primarily on home runs by Albert Pujols and Chris Duncan, the rookie son of the Cardinals pitching coach. Cards recovered and won the game primarily on home runs by Albert Pujols and Chris Duncan, the rookie son of the Cardinals pitching coach. So, the series returned to New York with St. Louis holding a 3-2 lead, much to the chagrin of, not just the Mets and their fans, but most of the baseball world as well. The prevailing theme of the day in sports pages across the country--except of course in the Post-Dispatch--was that this travesty was not supposed to be happening; the Cardinals as a 83-78 team in the regular season didn't even deserve to be in the post-season much less be squeezing the throat of "best" team in the National League. Things were looking good for the Redbirds as they had the current Cy Young winner starting Game 6. Unfortunately Chris Carpenter didn't have his best stuff and the Mets won 4-2 to force a Game 7. Jeff Suppan started the game for the Cardinals and again pitched brilliantly for over seven innings. Although St. Louis threatened throughout the early innings, they failed to  break though, primarily because of a spectacular play

by the Mets unheralded outfielder, Endy Chavez. In the sixth

inning with Jim Edmonds on first, Scott Rolen--who was finally healthy

and on the verge of breaking out of his late season slump--lined a shot

that was at least two feet above the left field wall.

Amazingly, Chavez, who had been playing Rolen well, got to the warning

track, leaped high into the air, stuck his glove over the fence, and to

everyone's astonishment, including his own, caught the ball. Jim

Edmonds, who was halfway to third, was so surprised that he couldn't

return to first in time, and was caught in a double play. The

Mets and their fans were psyched. Jose Reyes, the Mets shortstop, spent much of the rest

of the game dancing in the dugout to the delight of the fans who incessantly chanted his

name, and

the crowd noise at Shea reached a deafening roar and stayed that way

until the top of the ninth inning with the score tied 1-1. break though, primarily because of a spectacular play

by the Mets unheralded outfielder, Endy Chavez. In the sixth

inning with Jim Edmonds on first, Scott Rolen--who was finally healthy

and on the verge of breaking out of his late season slump--lined a shot

that was at least two feet above the left field wall.

Amazingly, Chavez, who had been playing Rolen well, got to the warning

track, leaped high into the air, stuck his glove over the fence, and to

everyone's astonishment, including his own, caught the ball. Jim

Edmonds, who was halfway to third, was so surprised that he couldn't

return to first in time, and was caught in a double play. The

Mets and their fans were psyched. Jose Reyes, the Mets shortstop, spent much of the rest

of the game dancing in the dugout to the delight of the fans who incessantly chanted his

name, and

the crowd noise at Shea reached a deafening roar and stayed that way

until the top of the ninth inning with the score tied 1-1. That changed in the ninth when Scott Rolen reached first  on a sharp single to left with one out, and catcher Yadier Molina, who struggled offensively throughout the regular season

but had picked it up considerably in the playoffs, stepped to the plate

to face the Mets star reliever, Billy Wagner. On Wagner's first

pitch, Molina blasted a towering home run over the left field wall,

giving

the Cardinals a two run lead. Shea Stadium fell absolutely

silent. on a sharp single to left with one out, and catcher Yadier Molina, who struggled offensively throughout the regular season

but had picked it up considerably in the playoffs, stepped to the plate

to face the Mets star reliever, Billy Wagner. On Wagner's first

pitch, Molina blasted a towering home run over the left field wall,

giving

the Cardinals a two run lead. Shea Stadium fell absolutely

silent. Rookie Adam Wainwright, who had been pressed into the closer's role after Isringhausen was injured, came into the game in the bottom half of the inning. Although he pitched fairly well, two singles and a walk loaded the bases with two outs and brought the Cardinal-killer, Carlos Beltran, to the plate. By this time, the fans at Shea were once more going wild;  there

was little doubt in their minds, nor probably in the minds of most

sportswriters, that the Mets were soon going get the win they so justly

"deserved." On television, Tim McCarver and Joe Buck bantered

about how Beltran

might likely drive in three runs with an extra base hit to win the

game. Instead, they all should have remembered Casey at the

Bat. After taking a first strike and foul tipping the next

pitch into the dirt, Beltran stood helplessly in the

batter's box, apparently paralyzed as Wainwright's third pitch, a slow

curve, broke over the outside corner of the plate. Beltran's bat

never even twitched; Molina sprinted to the mound to hug Wainwright;

the baseball establishment was stunned; the Cardinals had won their

second pennant in three years; and there was no joy in Metville, mighty Carlos had struck out. there

was little doubt in their minds, nor probably in the minds of most

sportswriters, that the Mets were soon going get the win they so justly

"deserved." On television, Tim McCarver and Joe Buck bantered

about how Beltran

might likely drive in three runs with an extra base hit to win the

game. Instead, they all should have remembered Casey at the

Bat. After taking a first strike and foul tipping the next

pitch into the dirt, Beltran stood helplessly in the

batter's box, apparently paralyzed as Wainwright's third pitch, a slow

curve, broke over the outside corner of the plate. Beltran's bat

never even twitched; Molina sprinted to the mound to hug Wainwright;

the baseball establishment was stunned; the Cardinals had won their

second pennant in three years; and there was no joy in Metville, mighty Carlos had struck out.The Cardinals had barely finished celebrating on the Shea Stadium infield before sportscasters began bemoaning the fact the Mets would not  represent the National League against Detroit in

the World Series. There was no way, they complained, that the

Cardinals could compete with the Tigers. The next day, almost

every baseball

writer and sportscaster in the national media predicted that the

Cardinals would lose to the powerful Detroit team, winning at most only

one or two games. One commentator stated, "It's not a question if

the Cardinals can win the World Series, it's a question of whether or

not the Cardinals can even win a game." And some moron writing

for USAToday decreed that the Cardinals were so undeserving and

overmatched that the well-rested Tigers, who had quickly advanced

through their playoff schedule, would take the series in only three

games. LaRussa and the Cardinals, to say the least, weren't so

sure. represent the National League against Detroit in

the World Series. There was no way, they complained, that the

Cardinals could compete with the Tigers. The next day, almost

every baseball

writer and sportscaster in the national media predicted that the

Cardinals would lose to the powerful Detroit team, winning at most only

one or two games. One commentator stated, "It's not a question if

the Cardinals can win the World Series, it's a question of whether or

not the Cardinals can even win a game." And some moron writing

for USAToday decreed that the Cardinals were so undeserving and

overmatched that the well-rested Tigers, who had quickly advanced

through their playoff schedule, would take the series in only three

games. LaRussa and the Cardinals, to say the least, weren't so

sure. LaRussa gambled in Game 1 and started rookie pitcher

Anthony Reyes, who

had been pressed into service in the rotation following Mark Mulder's

injury during the regular season. Initially it looked like

LaRussa had made a mistake as the Tigers pounced on Reyes in their half

of the first, but by the time the dust cleared they had only scored one

run. That lead, however didn't last long as Scott Rolen led off

the second with a home run. In the third, Chris Duncan doubled in

a run and Albert Pujols hit a two run blast to make the score

4-1.

Reyes, meanwhile, was phenomenal retiring 17 Tigers in a row. The

Cardinals added three more runs in the sixth and finished with a

surprisingly easy victory, 7-1. LaRussa gambled in Game 1 and started rookie pitcher

Anthony Reyes, who

had been pressed into service in the rotation following Mark Mulder's

injury during the regular season. Initially it looked like

LaRussa had made a mistake as the Tigers pounced on Reyes in their half

of the first, but by the time the dust cleared they had only scored one

run. That lead, however didn't last long as Scott Rolen led off

the second with a home run. In the third, Chris Duncan doubled in

a run and Albert Pujols hit a two run blast to make the score

4-1.

Reyes, meanwhile, was phenomenal retiring 17 Tigers in a row. The

Cardinals added three more runs in the sixth and finished with a

surprisingly easy victory, 7-1.Game 2 found Jeff Weaver facing Detroit's Kenny Rogers. Rogers, a mediocre postseason pitcher until 2006, had been on a roll so far in the playoffs, putting in stellar performances against the New York Yankees and Oakland Athletics. While Weaver pitched well, Rogers pitched better, and the Tiger chalked up a 3-1 win, which may have still been the case even if Rogers had not loaded up his pitching  hand with pine tar. Although Rogers removed the tar

from his hand once it was discovered, the umpires never checked his

hat, belt, glove, sleeves, or anywhere else to see just where he may

have hidden other stashes of the foreign substance. hand with pine tar. Although Rogers removed the tar

from his hand once it was discovered, the umpires never checked his

hat, belt, glove, sleeves, or anywhere else to see just where he may

have hidden other stashes of the foreign substance.The series moved to St. Louis for Game 3, which was started by Chris Carpenter. Carpenter pitched eight shut-out innings and the Redbirds cruised to a 5-0 victory with Jim Edmonds driving in two runs in the fourth on a bases-loaded double and the Detroit pitchers contributed three insurance runs on a throwing error and a wild pitch. In Game 4, Detroit started off strong and held a 3-0 lead in the third  inning.

St. Louis cut that lead to one

run by the end of the

fourth with run scoring doubles by Eckstein and Molina. In the

seventh, the Cardinals plated two more runs. Eckstein doubled and

then scored on a perfect sacrifice bunt by So Taguchi that the Detroit

pitcher threw over the head of the first basemen. Taguchi, in

turn, was driven in on a two-out single to left by outfielder Preston

Wilson. The teams traded runs in eighth and the game ended 5-4 as

the Cardinals took a three games to one lead in the series.

Sports journalists again were agog and appalled that little David

Eckstein and the Cardinals--a

team with only 83 victories in the regular season--were manhandling the

Tigers, darlings of the national media, and needed only one more win to

capture the title. This the press predicted was unlikely for

Kenny Rogers would lead the Tigers to victory in Game 5, and then the

series

would return to Detroit where the Tigers would find renewed purpose and

win the final two games. inning.

St. Louis cut that lead to one

run by the end of the

fourth with run scoring doubles by Eckstein and Molina. In the

seventh, the Cardinals plated two more runs. Eckstein doubled and

then scored on a perfect sacrifice bunt by So Taguchi that the Detroit

pitcher threw over the head of the first basemen. Taguchi, in

turn, was driven in on a two-out single to left by outfielder Preston

Wilson. The teams traded runs in eighth and the game ended 5-4 as

the Cardinals took a three games to one lead in the series.

Sports journalists again were agog and appalled that little David

Eckstein and the Cardinals--a

team with only 83 victories in the regular season--were manhandling the

Tigers, darlings of the national media, and needed only one more win to

capture the title. This the press predicted was unlikely for

Kenny Rogers would lead the Tigers to victory in Game 5, and then the

series

would return to Detroit where the Tigers would find renewed purpose and

win the final two games. Kenny Rogers, however, did not start Game 5. Detroit manager, Jim Leyland, was afraid to start Rogers in St. Louis, knowing full well that he would face an extremely hostile crowd who would not let him forget he had been caught cheating in the Tiger's  Game 2

victory. Instead Leyland started rookie pitcher, Justin

Verlander,

the Game 1 loser, and from early on it was clear the Tigers would have a rough night.

Verlander threw two wild pitches and walked

three men in the first, and although the Cardinals didn't score, the

tone was set for the rest of the game. Eckstein singled in a run

in

the following inning, and although the Tigers took a one run lead when

they followed a Chris Duncan error with a

home run, the Cardinals quickly got those two runs back when Eckstein

followed up a another run-scoring error by

the Detroit pitching staff with another run-scoring base hit of his

own. The Redbirds then added an insurance run when Scott Rolen

singled in Eckstein from second. The Tigers threatened in the

ninth inning putting the tying runs on first and third with two outs,

but Adam Wainwright quickly struck out Brandon Inge with an 0-2

curveball for the final out. St.

Louis had won its first world

series since 1982 in the new stadium's inaugural year, and the town

went

wild. Game 2

victory. Instead Leyland started rookie pitcher, Justin

Verlander,

the Game 1 loser, and from early on it was clear the Tigers would have a rough night.

Verlander threw two wild pitches and walked

three men in the first, and although the Cardinals didn't score, the

tone was set for the rest of the game. Eckstein singled in a run

in

the following inning, and although the Tigers took a one run lead when

they followed a Chris Duncan error with a

home run, the Cardinals quickly got those two runs back when Eckstein

followed up a another run-scoring error by

the Detroit pitching staff with another run-scoring base hit of his

own. The Redbirds then added an insurance run when Scott Rolen

singled in Eckstein from second. The Tigers threatened in the

ninth inning putting the tying runs on first and third with two outs,

but Adam Wainwright quickly struck out Brandon Inge with an 0-2

curveball for the final out. St.

Louis had won its first world

series since 1982 in the new stadium's inaugural year, and the town

went

wild.  Later

that week, the satirical newspaper, The Onion, published a article

ridiculing the sports journalists for their coverage of the Cardinals

in the post-season. Incredibly, after this article was

published on-line and reprinted in websites and in newspapers around

the country, an amazing number of people believed it was true. Later

that week, the satirical newspaper, The Onion, published a article

ridiculing the sports journalists for their coverage of the Cardinals

in the post-season. Incredibly, after this article was

published on-line and reprinted in websites and in newspapers around

the country, an amazing number of people believed it was true.For more information: |