Illuminations, Epiphanies, & Reflections

Branch Rickey

&

Gas

House Baseball

|

Following a horrendous,

but thankfully short, professional career as a catcher with the St.

Louis Browns of the American League, Branch Rickey left

baseball

to earn a law degree. He subsequently returned to the Browns as a

manager in 1912, but after two marginal season, he was fired when new

management took over the club. He returned to baseball in 1919

following his World War I service and became the President and Manager

of the St. Louis Cardinals. When Sam Breadon bought the team in

1920, Rickey relinquished the presidency but retained the field and

business manager duties for himself. Rickey and Breadon convinced

the American League St. Louis Browns to lease space at their

Sportsman's Park on Grand Avenue, the same field vacated by Von der Ahe

years before. Then, they then sold the

Cardinals' Vandeventer Avenue park to the city, and without much

fanfare Rickey

used the proceeds

to begin purchasing controlling interest in several minor league clubs;

a move that set the stage for Cardinal success throughout the 1930s and

1940. baseball

to earn a law degree. He subsequently returned to the Browns as a

manager in 1912, but after two marginal season, he was fired when new

management took over the club. He returned to baseball in 1919

following his World War I service and became the President and Manager

of the St. Louis Cardinals. When Sam Breadon bought the team in

1920, Rickey relinquished the presidency but retained the field and

business manager duties for himself. Rickey and Breadon convinced

the American League St. Louis Browns to lease space at their

Sportsman's Park on Grand Avenue, the same field vacated by Von der Ahe

years before. Then, they then sold the

Cardinals' Vandeventer Avenue park to the city, and without much

fanfare Rickey

used the proceeds

to begin purchasing controlling interest in several minor league clubs;

a move that set the stage for Cardinal success throughout the 1930s and

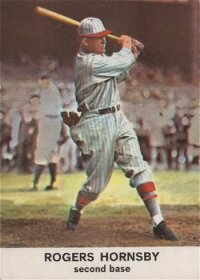

1940.Rickey led the Cardinals to mediocre records during the early 1920s until Breadon replaced him as the field manager with Rogers Hornsby in 1926. Rickey, however, stayed on to manage the team's business operations including player  development. Hornsby had been a popular Cardinal

star for years and routinely led the league in hitting, winning the

Triple Crown in 1922 and 1925 and batting .424 in 1924. Hornsby

continued to play second base while managing the team. Although a

fan favorite, Hornsby's attitude chaffed most of his team

members. He was abrasive, rude, and inconsiderate. If

you've seen A League of Their Own,

you probably remember the scene when Jimmy Dugan tells Doris Murphy, "Rogers

Hornsby was my manager, and he called me a talking pile of

pigshit. And that was when my parents drove all the way down from

Michigan to see me play the game. And did I cry?

. . . No! No! And do you know why? . .

. Because there's no crying in baseball. There's no crying

baseball. No crying!" Despite

Hornsby's less than stellar social skills, it was clearly his drive

and determination that led the Cardinals to their first National

League pennant in 1926. development. Hornsby had been a popular Cardinal

star for years and routinely led the league in hitting, winning the

Triple Crown in 1922 and 1925 and batting .424 in 1924. Hornsby

continued to play second base while managing the team. Although a

fan favorite, Hornsby's attitude chaffed most of his team

members. He was abrasive, rude, and inconsiderate. If

you've seen A League of Their Own,

you probably remember the scene when Jimmy Dugan tells Doris Murphy, "Rogers

Hornsby was my manager, and he called me a talking pile of

pigshit. And that was when my parents drove all the way down from

Michigan to see me play the game. And did I cry?

. . . No! No! And do you know why? . .

. Because there's no crying in baseball. There's no crying

baseball. No crying!" Despite

Hornsby's less than stellar social skills, it was clearly his drive

and determination that led the Cardinals to their first National

League pennant in 1926. St. Louis faced Babe Ruth and the Yankees in the 1926 series, and few thought the Cardinals had much of a chance against Murderers' Row. To everyone's surprise, the series came down to Game Seven. With bases loaded and two outs in the bottom of the seventh inning, and leading by only one run, Hornsby brought in old Grover Cleveland "Pete" Alexander to try and save the game.  Alexander had been sold to the Cardinals in mid-season by the Chicago Cubs, who had decided to no longer put up with his bouts of sullen drunkenness. Alexander had already pitched two complete game wins in the series, holding the Yankees to two runs apiece in Games Two and Six. As reported by Time Magazine, following Alexander's Game Six win, Hornsby relaxed his strict control over Pete's drinking and allowed him to spend the night on the town. As a result, Alexander was sleeping it off in the bullpen when Hornsby called on him to pitch in the seventh. As Alexander approached Hornsby near the mound after walking in from the bullpen, Rogers said, "Well, we're up 3-2, Pete, bases loaded, two out. Whatta ya think?" Alexander responded, "Guess there's no  place to put

him, eh Rog?"

He then struck out the Yankee slugger, Tony Lazzeri, to end the inning

and pitched two more scoreless innings to save the game and win

the

Series for St. Louis. place to put

him, eh Rog?"

He then struck out the Yankee slugger, Tony Lazzeri, to end the inning

and pitched two more scoreless innings to save the game and win

the

Series for St. Louis. Later, when asked about facing Lazerri, Alexander spoke of his second pitch to the  slugger, which Lazzeri

lined just foul into the outfield

stands down the third-base line, "A foot made the difference between

being a hero or a bum." (In

1952, Alexander's triumph of 1926 was made into a movie starring Ronald

Regan titled, The

Winning Team, which was,

in-turn, was referenced in the lyrics of Terry Cashman's 1982 hit song

during the early years of Regan's presidency, Talkin' Baseball: "And the great Alexander is pitchin' again in

Washington.") slugger, which Lazzeri

lined just foul into the outfield

stands down the third-base line, "A foot made the difference between

being a hero or a bum." (In

1952, Alexander's triumph of 1926 was made into a movie starring Ronald

Regan titled, The

Winning Team, which was,

in-turn, was referenced in the lyrics of Terry Cashman's 1982 hit song

during the early years of Regan's presidency, Talkin' Baseball: "And the great Alexander is pitchin' again in

Washington.")

Interestingly, Rogers Hornsby made the final putout of the series when he tagged out a sliding Babe Ruth at second; Ruth, who was never very fleet afoot, had for some inexplicable reason attempted to steal the base with Bob Meusel at the plate.  Alexander

continued to pitch well for St. Louis for several more years until his

alcoholism finally got the better of him. Hornsby on the other

hand was traded by Breadon and Rickey at the height of his career to

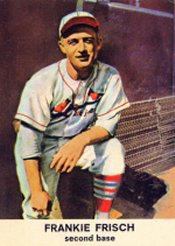

the New York Giants for a younger second baseman, Frankie Frisch.

Frisch had starred at second base for the Giants since 1919, but became expendable after an ugly and public falling out with John  McGraw.

Upon his trade to the Cardinals, Frisch immediately began to pay big

dividends, and fans soon forgot about the loss of Rogers Hornsby.

Although, Bill McKechnie, Billy Southworth, and eventually Gabby

Street became managers of the team, Frisch was the heart and soul of

Cardinal baseball in the 1930s and

led what was to become known as the Gas House Gang, consisting of

numerous home-grown, Branch

Rickey minor leaguers including Ripper Collins, the Dean brothers,

Pepper Martin, and Joe Medwick, to four National League championships

in 1928,

1930, 1931, and 1934 with World Series Titles in 1931 and 1934. McGraw.

Upon his trade to the Cardinals, Frisch immediately began to pay big

dividends, and fans soon forgot about the loss of Rogers Hornsby.

Although, Bill McKechnie, Billy Southworth, and eventually Gabby

Street became managers of the team, Frisch was the heart and soul of

Cardinal baseball in the 1930s and

led what was to become known as the Gas House Gang, consisting of

numerous home-grown, Branch

Rickey minor leaguers including Ripper Collins, the Dean brothers,

Pepper Martin, and Joe Medwick, to four National League championships

in 1928,

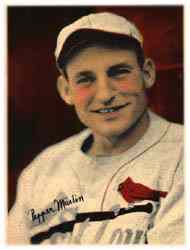

1930, 1931, and 1934 with World Series Titles in 1931 and 1934.The World Championship title in 1931 was a surprise once more even though Gabby Street's Redbirds had won 101 games during the season and left the second place New York Giants in their dust and thirteen games behind. They were give little chance against the American League Champion, Connie Mack's Philadelphia Athletics. However, as often has been the case in Cardinal history, the players didn't seem to realize that they had no chance. Cardinal pitching, led by Burleigh Grimes and Wild Bill Hallahan overwhelmed the As, and Johnny Leonard Roosevelt "Pepper" Martin, "the Wild Horse of the Osage," went crazy at the plate. Martin--one of the most colorful characters ever to wear a Cardinal uniform and informal leader of the famed Gas House Gang, which included a number of other "ruffians," most notably, Leo "the Lip" Durocher, Joe "Ducky" Mediwick, and Jerome "Dizzy" Dean--batted .500 during the series with twelve hits, five stolen bases, and five rbi's. Martin also led the  Cardinals' hillbilly jug band, the Mississippi Mudcats,

which performed locally in St. Louis, appeared on at least one national

radio broadcast, and even gave a few performances while the team was on

the road until management stepped in and suggested the athletes

concentrate on their on-field performance. Nothing is more

indicative of Martin's fiery temperament than an incident that happened

following his major league career while he was managing one of the

Cardinals' farm teams. In a rage after an umpire blew a call,

Martin grabbed the man by the throat and began to throttle him until he

was restrained by teammates. Later, he was called before the

Commissioner, who rhetorically asked, "Pepper, what in the world could

you have been thinking when you grabbed that umpire by the

throat?" "What was I thinking?" Martin replied, "I was thinking I

was going to choke that SOB to death." Cardinals' hillbilly jug band, the Mississippi Mudcats,

which performed locally in St. Louis, appeared on at least one national

radio broadcast, and even gave a few performances while the team was on

the road until management stepped in and suggested the athletes

concentrate on their on-field performance. Nothing is more

indicative of Martin's fiery temperament than an incident that happened

following his major league career while he was managing one of the

Cardinals' farm teams. In a rage after an umpire blew a call,

Martin grabbed the man by the throat and began to throttle him until he

was restrained by teammates. Later, he was called before the

Commissioner, who rhetorically asked, "Pepper, what in the world could

you have been thinking when you grabbed that umpire by the

throat?" "What was I thinking?" Martin replied, "I was thinking I

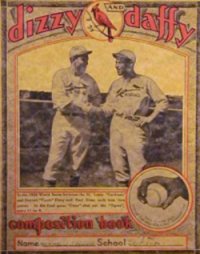

was going to choke that SOB to death."While the origin of the Gas House Gang nickname is somewhat unclear, and baseball historians are even in disagreement as to which of the Cardinal teams it was first applied, there is no doubt that it was a direct reference to an especially violent 19th century gang from the Gashouse neighborhood of New York City (Think Gangs of New York if you've seen that movie.) Legend has it that a New York sportswriter coined the nickname by writing that the players looked like "the gang from around the gashouse" when the team did not have time to launder its uniforms during one of its road trips and arrived at the Polo Grounds looking dirty and shabby. Leo Durocher related the incident in his autobiography, remembering that "the next day, I saw a cartoon in the World-Telegram. It showed two big gas tanks on the wrong side of the railroad track, and some ballplayers crossing over to the good part of town carrying clubs over their shoulders instead of bats. And the title read: 'the Gashouse Gang.'" That cartoon, was drawn by Willard Mullin, the dean of American sports cartoons, and once it was published, the team would never loose its nickname.   Prior to the start of the season, Jerome "Dizzy" Dean predicted that he and

his brother, Paul "Daffy" Dean, would win 45 games for the

Cardinals. Amazingly, they combined for a total of 49 wins; 30

for Dizzy and 19 for Daffy. That was over half of the Cardinals

regular season wins, and the team needed each of them as it didn't

clinch the

pennant until the final day of the season. The brothers kept up

their pace

against the Detroit Tigers, combining for the Cardinals' four wins and

recording 28 strikeouts and a joint ERA of 1.34. "Ole Diz's"

story was made into a very funny movie starring Dan Dailey, Pride

of St Louis Prior to the start of the season, Jerome "Dizzy" Dean predicted that he and

his brother, Paul "Daffy" Dean, would win 45 games for the

Cardinals. Amazingly, they combined for a total of 49 wins; 30

for Dizzy and 19 for Daffy. That was over half of the Cardinals

regular season wins, and the team needed each of them as it didn't

clinch the

pennant until the final day of the season. The brothers kept up

their pace

against the Detroit Tigers, combining for the Cardinals' four wins and

recording 28 strikeouts and a joint ERA of 1.34. "Ole Diz's"

story was made into a very funny movie starring Dan Dailey, Pride

of St Louis The most

memorable moment of the 1934 Series occurred in the sixth inning of Game

7. The

Cardinals were already blowing out the Tigers with a

9-0 lead, when Joe "Ducky"

"Muscles" Medwick, who had led the team's offense during series hitting

.379 with a homerun

and five RBIs,

slid hard into the Tiger third basemen

incurring the

wrath of the frustrated Tiger fans. In the bottom half of the

inning, when

Medwick took his position in left field, the

Tiger fans began to bombard him with bottles, fruit, vegetables, and other debris.

Baseball Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis, who was watching from

the stands decided to order the removal of Medwick from the game for

his

own protection rather

than cause the Tigers to forfeit. That decision, of course, did

not sit well with the Cardinals, but it didn't matter. The final

score was 11-0 as the Cardinals won another World Series. The most

memorable moment of the 1934 Series occurred in the sixth inning of Game

7. The

Cardinals were already blowing out the Tigers with a

9-0 lead, when Joe "Ducky"

"Muscles" Medwick, who had led the team's offense during series hitting

.379 with a homerun

and five RBIs,

slid hard into the Tiger third basemen

incurring the

wrath of the frustrated Tiger fans. In the bottom half of the

inning, when

Medwick took his position in left field, the

Tiger fans began to bombard him with bottles, fruit, vegetables, and other debris.

Baseball Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis, who was watching from

the stands decided to order the removal of Medwick from the game for

his

own protection rather

than cause the Tigers to forfeit. That decision, of course, did

not sit well with the Cardinals, but it didn't matter. The final

score was 11-0 as the Cardinals won another World Series.For more information: |