|

Illuminations, Epiphanies, & Reflections

The Von der Ahe

Years

Long before the Cardinals

were the Cardinals, baseball was played in St. Louis.  Shepard

Barclay, who was to eventually become a justice on

the Missouri Supreme Court, once recalled that a contractor from "back

east," named Jere Frain, came to St. Louis in the early 1850s.

Along with him, Frain (who had been a ball player with the Charter Oak

Base Ball Nine of Hartford) brought a passion for the new sport.

Unfortunately for Frain, the national craze had not yet reached St.

Louis, so he decided to recruit players himself. Starting from

scratch, he laid out a diamond in Lafayette Park and taught the game

to any of the boys and young men in the neighborhood who were interested. By the mid-1860s, a

handful of amateur baseball clubs had been

founded, including the Red Stockings, the Atlantics, the Empires and

the Unions. Shepard

Barclay, who was to eventually become a justice on

the Missouri Supreme Court, once recalled that a contractor from "back

east," named Jere Frain, came to St. Louis in the early 1850s.

Along with him, Frain (who had been a ball player with the Charter Oak

Base Ball Nine of Hartford) brought a passion for the new sport.

Unfortunately for Frain, the national craze had not yet reached St.

Louis, so he decided to recruit players himself. Starting from

scratch, he laid out a diamond in Lafayette Park and taught the game

to any of the boys and young men in the neighborhood who were interested. By the mid-1860s, a

handful of amateur baseball clubs had been

founded, including the Red Stockings, the Atlantics, the Empires and

the Unions.

In 1867, the Washington Nationals, a second tier

Eastern

club tired of being beaten to a pulp by the premier New York and

Brooklyn teams, barnstormed across the Midwest leaving a wake of

destruction as it passed cities in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and

Kentucky. Newspaper accounts of the trip report incredibly

lopsided defeats of the hastily assembled hometown teams. The

Nationals visit to St. Louis was no exception as they left

town with a resounding 113-26 victory over the most powerful of the

local teams, the Unions. St. Louis, however, was

left with a thirst for more baseball, and amateur clubs flourished in

the city for the the next decade.

In 1874, however, a St. Louis business man, James R. Lucas, announced

that he had raised

$10,000 in capital by selling $50 shares in order to register a team in

the National Association of of Professional Baseball Players, and the following year, the St. Louis Brown Stockings entered the league. Their first game was against a local amateur team, the St. Louis Red Stockings, on 4 May

1875 at the Red Stocking's field on Compton Avenue and Gratiot

Street. Not surprisingly, the Brown Stockings won easily by a score of 15-9. league. Their first game was against a local amateur team, the St. Louis Red Stockings, on 4 May

1875 at the Red Stocking's field on Compton Avenue and Gratiot

Street. Not surprisingly, the Brown Stockings won easily by a score of 15-9.

One of the best teams in the country, the undefeated Boston Red

Stockings, visited St. Louis later that summer sporting a 26 game

winning streak and were surprised by the upstart Brown Stockings at the

old North Grand Avenue baseball field, which in time would become

Sportsman's Park and later Busch Stadium, losing the game 5-4. By

far the biggest game of the year, though, was a home game played

against the Chicago White Stockings, the team that eventually became

the

Chicago Cubs. St. Louis won the game much to the delight of the 5,000 spectators who packed the park

and ended up in fourth place at the end of the year, a respectable

finish for its first year in the league.

In 1876, the team registered to play

as a charter member of the newly formed National League and again did quite well even though it had only one pitcher, George Washington "Grin"

Bradley, on its

roster. Bradley, by the way, pitched the first no-hitter in

professional baseball on 15 July, defeating the Hartford Dark Blues

2-0. He pitched every out of every game for the Brown

Stockings that season (535 2/3 innings) and ended with a

45-19 record as the team finished in second place. The League,

however had decided that to determine it's champion, the first and

second place teams would play five additional games against each other

with the winner of the series being christened The Champions of the

West. So, in the first true pre-cursor of the World Series, the

Brown Stockings/Cardinals played the White Stockings/Cubs. St.

Louis easily handled Chicago and won the championship four games to one. though it had only one pitcher, George Washington "Grin"

Bradley, on its

roster. Bradley, by the way, pitched the first no-hitter in

professional baseball on 15 July, defeating the Hartford Dark Blues

2-0. He pitched every out of every game for the Brown

Stockings that season (535 2/3 innings) and ended with a

45-19 record as the team finished in second place. The League,

however had decided that to determine it's champion, the first and

second place teams would play five additional games against each other

with the winner of the series being christened The Champions of the

West. So, in the first true pre-cursor of the World Series, the

Brown Stockings/Cardinals played the White Stockings/Cubs. St.

Louis easily handled Chicago and won the championship four games to one.

The team was

poised for an excellent season the following year

after it lured five superb players away from the Louisville Grays with

very lucrative salary offers. Unfortunately for the Brown

Stockings, four of the five players were implicated in baseball's first

gambling scandal from the season before and banned from baseball for

life. Now without a competitive roster for the year, the

remaining Brown Stockings withdrew from the league and continued to

play as amateurs.

In 1880 a saloon-keeper named Chris

von der Ahe, who owned an establishment near the Grand Avenue ballpark, noticed that business boomed at his tavern on game days when fans poured

in after spending oppressively hot summer afternoons in the uncovered

bleachers. He purchased controlling interest in the nearly defunct amateur Brown Stockings as

well as in the Grand Avenue field, which he renamed Sportsman's Park

and Club. Two

years later, von der Ahe purchased a franchise for his team as one of

the charter members of the old rough-and-tumble American Association,

known as the "Beer and Whiskey League" because of the alleged

rowdiness of its fans and the fact that many of its teams were owned or

sponsored by breweries and distilleries. oppressively hot summer afternoons in the uncovered

bleachers. He purchased controlling interest in the nearly defunct amateur Brown Stockings as

well as in the Grand Avenue field, which he renamed Sportsman's Park

and Club. Two

years later, von der Ahe purchased a franchise for his team as one of

the charter members of the old rough-and-tumble American Association,

known as the "Beer and Whiskey League" because of the alleged

rowdiness of its fans and the fact that many of its teams were owned or

sponsored by breweries and distilleries.

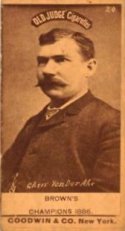

Von der Ahe, a German immigrant, with a larger-than-life

persona and a handlebar moustache to match, referred to himself as

"der Boss President," and he was certainly a good one. Von der

Ahe knew how to make money and billed himself as "The Millionaire

Sportsman." The Browns consistently led the American Association

in attendance and drew in fans with innovations such as on-site beer

sales (balls hit into

the right field beer garden were considered to be

in-play), hotdog vending

(well, sausage vending anyway), and

Sunday games.

Von

der Ahe's team was initially very

successful, compiling a 782-433 (.644) record in its first ten years,

winning the American Association pennant four

times from 1885-1888, and

defeating the National League Champion, the Chicago White

Stockings--now the Chicago Cubs--in the 1885 and 1886 World's

Championship Series.

1888 St. Louis Brown Stockings

The 1885 series was disputed after the fact

by the Chicago owner, Albert

Spalding (yes, that Spalding). In

the series' second game, the St. Louis player-manger, Charles Comiskey

(yes, that Comiskey) pulled his team off the field in protest of a

botched call by an umpire. The umpires initially decided to call

the game a forfeit, but

the two managers discussed the situation and agreed simply to ignore

the game

and continue the series. When Chicago lost the final game and the

Championship, three games to two, Spalding protested and refused to

allow the prize money--put up by the two owners and held in escrow--to

be

distributed. The only way for Von der Ahe to get his money back

was to submit to Spalding's blackmail and agree that the series was a

tie. series' second game, the St. Louis player-manger, Charles Comiskey

(yes, that Comiskey) pulled his team off the field in protest of a

botched call by an umpire. The umpires initially decided to call

the game a forfeit, but

the two managers discussed the situation and agreed simply to ignore

the game

and continue the series. When Chicago lost the final game and the

Championship, three games to two, Spalding protested and refused to

allow the prize money--put up by the two owners and held in escrow--to

be

distributed. The only way for Von der Ahe to get his money back

was to submit to Spalding's blackmail and agree that the series was a

tie.

Troubles, however, began to mount, beginning in 1887, when Von der Ahe

threatened to deny his players their earnings because of their poor

performance in that year's World's Championship

series. Soon

thereafter,

he dismissed Comiskey and began managing the team himself. The

Brown's performance plummeted, and other legal

problems began to suck

away at his capital. In 1892, when the American Association

folded, the Browns joined the National League, and--hoping

to increase revenue--Von der Ahe moved the team to a sports complex he

built at Vandeventer and Natural Bridge, which he named the New

Sportsman's Park. With a marketing imagination that would not be

equaled until the arrival of Bill Veeck, Von der Ahe constructed "the

Coney Island of the West," which not only contained the ballpark but

included a beer

garden, a chute-the-chute water ride, an outfield track for night time

horse racing, and an

artificial lake. He hired an all female concert orchestra--the

Silver Comet Band--to provide

entertainment by playing popular songs of the day, and used the

facility to host other events, the most

spectacular being a "double-header" that combined a ball game with

Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show when it visited St. Louis after returning

from a European tour. began to suck

away at his capital. In 1892, when the American Association

folded, the Browns joined the National League, and--hoping

to increase revenue--Von der Ahe moved the team to a sports complex he

built at Vandeventer and Natural Bridge, which he named the New

Sportsman's Park. With a marketing imagination that would not be

equaled until the arrival of Bill Veeck, Von der Ahe constructed "the

Coney Island of the West," which not only contained the ballpark but

included a beer

garden, a chute-the-chute water ride, an outfield track for night time

horse racing, and an

artificial lake. He hired an all female concert orchestra--the

Silver Comet Band--to provide

entertainment by playing popular songs of the day, and used the

facility to host other events, the most

spectacular being a "double-header" that combined a ball game with

Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show when it visited St. Louis after returning

from a European tour.

Unfortunately

his debts continued to mount, and Von der Ahe sold most

of his best players to the Brooklyn Bridegrooms. Subsequently,

after an expensive divorce, he began to resort to loans from shady

characters, and after reneging on one, he was kidnapped and

ransomed. In 1898, a suspicious fire burned New Sportsman's Park

to the ground, and though he rebuilt a much simpler replacement on the

same spot, Von der Ahe eventually lost it and his team in the resulting

civil

trial. Unfortunately

his debts continued to mount, and Von der Ahe sold most

of his best players to the Brooklyn Bridegrooms. Subsequently,

after an expensive divorce, he began to resort to loans from shady

characters, and after reneging on one, he was kidnapped and

ransomed. In 1898, a suspicious fire burned New Sportsman's Park

to the ground, and though he rebuilt a much simpler replacement on the

same spot, Von der Ahe eventually lost it and his team in the resulting

civil

trial.

The team then changed owners and names twice

in quick succession, first being rechristened the Perfectos.

Then,

after a sportswriter reported upon a lady's comments about the

interesting shade of red piping on the team's new uniforms, they became

known as the Cardinals. Cleveland street car entrepreneurs, Frank

and Stanley Robinson ended up as team owners in 1899. The

Robinsons also owned Cleveland's National League franchise, the

Spiders, which was doing horribly at the gate. In what amounted

to a near wholesale transfer of players, the Robinsons sent most of

the best Spiders to the Vandeventer Park--which had been renamed

Robinson Field, where they became first

the Perfectos and then the Cardinals. The team then changed owners and names twice

in quick succession, first being rechristened the Perfectos.

Then,

after a sportswriter reported upon a lady's comments about the

interesting shade of red piping on the team's new uniforms, they became

known as the Cardinals. Cleveland street car entrepreneurs, Frank

and Stanley Robinson ended up as team owners in 1899. The

Robinsons also owned Cleveland's National League franchise, the

Spiders, which was doing horribly at the gate. In what amounted

to a near wholesale transfer of players, the Robinsons sent most of

the best Spiders to the Vandeventer Park--which had been renamed

Robinson Field, where they became first

the Perfectos and then the Cardinals.

So, the renamed Cardinals

began their first season in St. Louis with handful of former Cleveland stars filling out the roster

including .400 hitting outfielder Jesse Burkett, super shortstop Bobby

Wallace, and pitcher Denton True "Cyclone"

Young. Interest in the revitalized team was strong, and the

Cardinals played their opening day on 15 April 1899 before a crowd of

18,000 at the rebuilt and renamed League Park on Vandeventer. Cy

Young took the mound on that first game, which was, by coincidence,

with the horrendous Spiders of Cleveland whose roster was filled with

the dregs of the 1898 Brown's team. In less than two hours, Cy

Young and the Cardinals had beaten Cleveland by the score of 10-1. handful of former Cleveland stars filling out the roster

including .400 hitting outfielder Jesse Burkett, super shortstop Bobby

Wallace, and pitcher Denton True "Cyclone"

Young. Interest in the revitalized team was strong, and the

Cardinals played their opening day on 15 April 1899 before a crowd of

18,000 at the rebuilt and renamed League Park on Vandeventer. Cy

Young took the mound on that first game, which was, by coincidence,

with the horrendous Spiders of Cleveland whose roster was filled with

the dregs of the 1898 Brown's team. In less than two hours, Cy

Young and the Cardinals had beaten Cleveland by the score of 10-1.

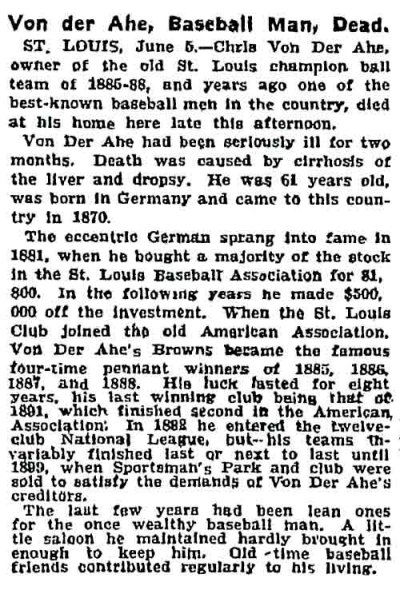

For a long time, I wondered whatever happened to Chris von der Ahe

after he lost the team and went bankrupt. Recently, I stumbled

upon a copy of his obituary published in the New York Times on 6 June 1913.

The statue above Von

der Ahe's grave at Bellfontaine Cemetery is one he commissioned to sit

outside the entrance to Sportsman's Park when his Brown Stockings were

in their

prime. At the time, the press ridiculed him for doing so; too bad

this likeness doesn't now stand outside Busch Stadium.

For more

information:

|

|