|

Illuminations and Epiphanies

Banned Books

A Chronological Collection of

Banned Books

The 1700s

|

An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding.

In

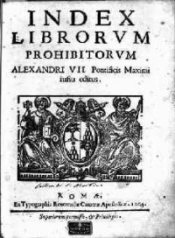

1700, the Catholic Church placed John Locke's An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding

on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum,

where it remained until 1951.

An Essay

argues that the minds of all newborns are blank slates and that all

ideas and thoughts are developed from experience. As a

corrollary,

Locke maintained that people have no innate principles including no

sense that God should be worshipped. He pointed out that mankind

does not even agree on a conception of God or even whether or not God

exists.

|

|

|

The Shortest Way with the Dissenters.

In 1702,

during the height of a debate in the House of Commons as to how to

detect Dissenters that hid their religious beliefs in order to secure

government office, Daniel Defoe published a satirical sermon, The Shortest Way with the Dissenters,

in which he pretended to be a high official within the Anglican Church

and advocated "Now, Let Us Crucify The Thieves!" and build a foundation

for the church upon "the destruction of her enemies." His essay

outraged all parties who missed the satire, and all copies of his

sermon, "being full

of false and scandalous Reflections upon this Parliament, and tending

to promote Seditions, [were ordered to be] burnt [by] the common

Hangman. . . ." When it was finally revealed that Defoe wrote the

essay as satire, he was fined, pilloried, and jailed in Newgate Prison.

|

|

|

Gulliver's Travels. If you

browse

any site on the internet that discusses banned books, or if you view

almost any library display during the ALA's Banned Book Week, you will

inevitably see Johnathan Swift's classic satire, Gulliver's Travels (the real title,

by the way, is Travels into Several

Remote Nations of the World), listed as having been banned in

one form or another almost from it's date of publication in 1726.

This claim, however, doesn't seem to be supported by any

evidence. Actually, the book was incredibly popular, and as

Alexander Pope noted it was "universally read, from the cabinet council

to the nursery." Even one of Swift's harshest critics, Samuel

Johnson, admitted that

It was

received with such avidity, that the price of the first edition was

raised before the second could be made; it was read by the high and the

low, the learned and illiterate. Criticism was for a while lost in

wonder; no rules of judgment were applied to a book written in open

defiance of truth and regularity.

So, from where does this notion that the book was banned arise?

Most likely from a lecture published in Victorian England by William

Makepeace Thackeray in which he branded parts of the work as "gibbering

shrieks, and gnashing imprecations against mankind--

tearing down all shreds of modesty, past all sense of manliness and

shame; filthy in word, filthy in thought, furious, raging,

obscene." While that may be true, there is no record of the book

having ever been banned, although children's editions are invariably

expurgated.

|

|

|

Sorrows of Young Werther.

Johann

Wolfgang von Goethe's classic story about suicide, Sorrows of Young Werther, was

published in 1744 and became very popular throughout Europe. Most

of the book is written as diary entries that describe the depression of

a young man. In the final chapter, Goethe switches to the third

person and describes Werther's suicide in graphic detail. When a

number of copycat suicides occurred, the book was condemned by the

Lutheran Church, after which it was banned in Denmark, Germany, and

Italy.

|

|

|

Fanny Hill. In 1748, John

Cleland was

arrested and sent to debtors' prison after a failed business

venture. There, he wrote the erotic novel, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (Fanny Hill),

that was to become synonymous with the censorship of "obscene"

materials. The book was published in two installments while

Cleland remained in prison, however after his release he, along with

the publisher, was arrested in November of 1749 and charged with

"corrupting the King's subjects." Both were

released after Cleland publicly renounced the book--as originally

written--and it was withdrawn from print. After

Cleland removed the most objectionable passages from the book,

including one that described Fanny's witnessing of a homosexual

encounter between two men, he was allowed to publish an expurgated

edition. The original version was also officially banned in the

United States in 1821 and remained so until 1966 when the United States

Supreme Court ruled that it should be allowed to be published as it did

not violate the Roth Standard for obscenity.

|

|

|

Tom Jones. Another title that

appears so

frequently on banned books lists you would think it almost impossible

to have ever survived is Henry Fielding's The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling

(more usually referred to as simply Tom

Jones), which was published in 1749. The book is a

collection of earthy, ribald, exciting, and humorous stories that

include prostitution and promiscuity. Yet, as with Gulliver's Travels, there is no

documentation that it was banned upon publication or later by the

United Kingdom or by the Catholic Church. Neither is there any

documentation that it was ever banned by the United States. There

are, however, several references to it having been banned in France,

but these are not substantiated with any details or sources.

Again, like Gulliver's Travels,

references to its banning may be based on the published opinion

of another author, Samuel Johnson, who once wrote to a friend, "I am

shocked to hear you quote from so vicious a book . . . I scarcely know

a more corrupt work."

|

|

|

Paradise Lost. John Milton

published his epic poem, Paradise

Lost,

in 1667 as, perhaps in part, a reflection on the defeat of Cromwell's

revolution and the restoration of the monarchy. In it, not only

does

Milton attempt to reconcile some elements of pagan and Christian

tradition, but he portrays Satan somewhat heroically as a proud, but

sympathetic, character who defies a rather tyrannical God and then

wages an unsuccessful war on His heavenly forces. It is

surprising

that the Catholic Church did not ban Milton's work sooner, but it was

not placed on the Index Librorum

Prohibitorum until 1758. |

|

|

Candide, or Optimism, was

pseudonymously authored by François-Marie Arouet (Voltaire) in

1759. That it was not popular with the Church

almost goes without

saying as in it there is a short reference to a fictional Pope being

the father of one characters. More damning perhaps was its

hilarious and scathing satirical attack on Gottfried

Wilhelm von Leibnitz's philosophy of optimism, which

argues that since God is perfect and God created everything in the

world, then everything in the world is perfect. It was placed on

the Index Librorum Prohibitorum

in 1762.

|

|

|

Emile, or On Education. In

1762, Jean-Jacques Rousseau published Emile,

or On Education, a philosophical novel that he considered to be

his best and most important work. In it, he addresses what he

believed to be the essential philosophical and political questions

regarding the relationship between naturally good individuals and the

inherently corrupt societies within which they live. In doing so,

Rousseau created the first philosophy of Western education. The

book was banned and burned immediately upon its publication in both

Paris and Geneva, primarily for the short and then infamous section,

"Profession of Faith of the Savoyard Vicar," in which Rousseau

describes both his religious views and a method for teaching them.

|

|

|

The Marriage of Figaro.

Pierre

Beaumarchais published the second volume in his trilogy of Figaro

plays, The Marriage of Figaro,

in 1781. Although it was originally approved by France's state

censor, King Louis XVI personally found the work's satire of the

aristocracy offensive and immoral. He imposed a ban on the play

and had Beaumarchais imprisoned for a short time. Upon his

release, Beaumarchis repeatedly rewrote the play in an attempt to

please Louis, and in 1784, the king finally lifted his ban. The

play was first performed later that year and became immensely popular,

even among the aristocracy. Mozart's opera of the same name was

based on Beaumarchais play and premiered in 1786.

|

|

|

The Age of Reason. Thomas

Paine

began his two-volume classic, The

Age of Reason, while imprisoned in revolutionary France in 1793

awaiting the guillotine for protesting the execution of King Louis

XVI. Paine was a deist, and although he rejected supernatural

religions like Christianity, he believed in a rational universe created

a benevolent God that operated on logical principles. The Age of

Reason expresses Paine's beliefs and aggressively argues against

Judeo-Christian religions and details the numerous inconsistencies

within both the Old and New Testaments. Interestingly, the book

was banned in France because it was viewed as too religious and in

England because its biblical challenges were viewed as too

atheistic.

|

|

To the 1600s

To the 1800s

|

|