|

Illuminations and Epiphanies

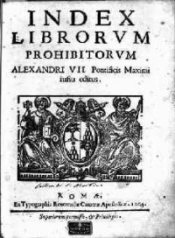

Banned Books

A Chronological Collection of

Banned Books

The 1600s

| |

The History of the World. Sir

Walter Raleigh, a favorite of Queen Elizabeth found himself in disfavor

for his political and religious views once James I became King.

He was sentenced to death on trumped-up treason charges in 1603 and

imprisoned indefinitely in the Tower of London awaiting his fate.

While imprisoned, he began work on his epic History of the World, which was as

much a political attack on the divine right of kings as an historical

work. According to one biographer, Raleigh “took

every opportunity he could in his book to pour scorn on famous

sodomites, and James took the point.” James, of course,

immediately banned the first volume of the work upon its publication,

noting that it was "too saucy in censuring princes." Raleigh was

beheaded in 1616 before he could complete his project's final two

volumes.

|

|

|

De

Revolutionibus and The Dialogue

Concerning the Two Chief World Systems. In 1610, Galileo

Galilei published a small book, Starry

Messenger, based on his telescopic observation of the

heavens. In it he described a number of observations that, while

not directly conflicting with the Aristotolean view of the universe

accepted by the Church, clearly caused Aristotelian supporter

considerable discomfort. Later he championed Nicolai Copernicus's

De Revolutionibus,

a heliocentric explanation the universe, to Catholic authorities in

hopes that the Church would adopt the theory. It did not, and De Reolutionibus, while not

technically banned, was identified as a book that required substantial

revision before it could be republished. Additionally, Galileo,

was formally ordered not to publicly advance or support a

sun-centered system of astronomy. Galileo avoided controversy for

a number of years but when a friend of his, Cardinal Barberini, became

Pope Urban VIII in 1623, he again began to advocate the Church's

acceptance of a heliocentric universe. He published his famous

work, The Dialogue Concerning the

Two Chief World Systems in 1632. Although he intended no

sarcasm, papal authorities believed the character, Simplicio, was

intended to ridicule Urban. Worse, Urban believed that

himself. Galileo was summoned to Rome to defend himself and

following his trial, in which he was threatened with being burned at

the stake, was placed under house arrest and once more forbidden to

ever publicly support a heliocentric position again.

Additionally, without fanfare, his Dialogue

was prohibited from any reprinting, and any of his future writings were

banned from publication and distribution.

|

|

|

|

In 1633,

William Prynne, a Puritan, published a heavy-handed criticism of the

London theater, the Histrio-Mastix

the Players Scourge, or Actors Tragaedie. Unfortunately

for Prynne, the book was released almost simultaneously with the

production of a play for the royal court. For some time, Prynne's

writings and tracks, which were critical of what he viewed as the lax

moral standards

of the court, the Church of England, and society in general, had

irritated the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud. Laud,

seizing the opportunity to end Prynne's writing once and for all,

brought the Histrio-Matrix to

the attention of Charles I and his wife, Queen Henrietta-Maria,

describing its contents, especially his description of actresses as

"notorious whores," as an attack upon the queen, who had occasionally

performed on stage. Prynne was arrested and tried for treason

before the Star Chamber. He was, of course, found guilty and

sentenced to be fined £5,000, pilloried,

branded, have both ears cut off, and then be imprisoned for life.

After pronouncing Prynne's sentence, Lord Cottington additionally

decreed:

I do in the

first place begin Censure with this Book. I condemn it to be burnt, in

the most publick manner that can be. The manner in other Countries is,

to be burnt by the Hang-man, though not used in England, (yet I wish it

may, in respect of the strangeness and hainousness of the matter

contained in it) to have a strange manner of burning; therefore I shall

desire it may be so burnt by the Hand of the Hang-man.

|

|

| |

Areopagitica: A speech of Mr John Milton

for the liberty of unlicensed printing to the Parliament of England.

With the Licensing Act of 1643, Parliament wrested control of the book

banning process from the throne. The Licensing Act required

authors to have their works pre-approved by the Stationers’ Company, a

firm that Parliament contracted with to serve as its censor in return

for a monopoly on the English printing trade. Although the subtitle of

this "speech" implies that it was given by Milton to Parliament, he did

not do so. In fact, Milton had always intended to distribute his

polemic throughout England in pamphlet form. Written at the

height of the First English Civil war, Areopagitca is an indictment

against the practice of requiring authors to obtain official approval

of their books before they could be published. Almost needless to

say, Milton did not request prior permission to publish his pamphlets

from the Stationer's Company. And, also almost needless to say,

the Aeropagitica was banned.

|

|

|

The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption,

Justification, Etc. by William Pinchin has the distinction of

being the first book to be banned in what is now the United

States. Pynchon published his book in 1650 as an argument to

refute the doctrine of atonement--the process for pardoning sin--as

established by the Westminster Assembly of Divines. The

General Court of Massachusetts found the argument so offensive that it

condemned all copies to be burned noting "having had the sight of a

booke lately printed under the name of William Pinchon in New England,

Gent., doe judge meete, first, that a protest be drawen, fully and

cleerely, to satisfy all men that this Courte is so farr from

approoving the same as they doe utterly dislike it and detest it as

erronjous and daingerous; secondly, that it be sufficjently answered by

one of the reverend elders; thirdly, that the sajd William Pinchon,

gent., be summoned to appeare before the next Generall Courte to answer

for the same; fowerthly, that the sajd booke now brought over be burnt

by the executioner, or such other as the magistrates shall appointe,

(the party being willing to doe it,) in the markett place in Boston, on

the morrow immedjately after the lecture."

|

|

|

Letters Provencial. In 1656,

Blaise Pascal published a series of 18 witty and polished letters that

attacked a form of ethical logic, known as casuistry, that was

practiced by the Jesuits. Casuistic reason is based on

case-by-case determinations as to what is ethical and what is

not. Pascal, in his Lettres

Provencial, argued that such reasoning was false and

amoral. Although the letters' mockery and biting satire of

mainstream Catholicism made them exceptionally popular, the book

outraged not only the Catholic establishment but King Louis XIV of

France as well, who ordered all copies to be shredded and burned.

|

|

|

Leviathan. In 1683,

following the Rye House Plot to kill King Charles II

and his brother James (which may have been a hoax perpetuated by

Charles

so that he could legally eliminate his opposition in Parliament),

Oxford University, on behalf of the court, issued The

Judgment and Decree of the University of Oxford Past in their

Convocation July 21, 1683 Against certain Pernicious Books and Damnable

Doctrines Destructive to the Sacred Persons of Princes, their State and

Government, and of all Humane Society. Among the titles

listed in this decree to be collected and burned was Leviathan, or the Matter, Form and Power

of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiastical and Civil by Thomas Hobbes.

Although Hobbes ideas of the state as an authoritative Leviathan with

absolute power and with whom all individual members of a nation grant

some of their natural rights of freedom in exchange for a guaranty of

internal peace and external defense, should have found considerable

favor with the Royalists, its secular nature offended both

Anglicans and Catholics alike.

|

|

|

To the 1500s To the 1700s

|

|