|

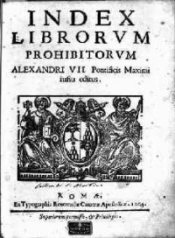

Illuminations and Epiphanies

Banned

Books

A Chronological Collection of

Banned Books

The 1900s

|

Three Weeks.

Founded in

1878 by John Frank Chase, the Watch and Ward Society of Boston's stated

goal was to "watch and ward off evildoers," specifically in the arts

and literature. Although this society of do-gooders was never

effective in getting the government to ban books, it did intimidate the

Boston Public Library from purchasing some titles as well as removing

some already purchased books from circulation. Generally,

though,

the society was regarded as a joke, and publishers could guarantee

additional sales of a book by announcing that it had been "banned in

Boston." The society only was able to instigate one

successful

court case, in 1907, that resulted in a single title, Elinor Glyn's Three Weeks, being

branded as

obscene. Among the titles it was unsuccessful in

getting a

court to ban were: Leaves

of

Grass by Walt Whitman, Elmer

Gantry by Sinclair Lewis, The

Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway, An American Tragedy

by Theodore

Dreiser, Mosquitos

by William

Faulkner, Manhattan

Transfer

by John Dos Passos, Oil

by

Upton Sinclair, and God's

Little

Acre by

Erskine Caldwell.

|

|

|

What Every Girl Should Know.

In 1912, the

U.S. Post Office, the executive agent for enforcing the Comstock Act,

banned the publication of Margaret Sanger's column, "What Every Girl

Should Know," in the weekly newspaper, The New York Call.

Although

the column included information on puberty, reproduction, and birth

control, it was an article about syphilis that drew the attention of

government censors. Several years later, the information that

Sanger had published in her columns was released in pamphlet form as

part of the famous Little Blue Book series. Although Sanger's

effort to spread the word about birth control were

exceptional, in recent years, her motives for doing so have been

tarnished by research that revealed her support of eugenics and the

mandatory sterilization of the "unfit" as well as entire groups of

peoples who had shown themselves to be "irresponsible and reckless."

Other writings and speeches by Sanger and her cohorts clearly have

revealed that she specifically included Catholics and African-Americans

in these groups. Not

surprisingly, publication of this research, such as Killer Angel by

George Grant, has

occasionally been banned by local librarians in an effort to

protect Sanger's reputation.

|

|

|

Can Such Things Be. Ambrose Bierce's collection

of eerie supernatural tales, Can Such Things Be, is another title

that seems to appear on every "banned books" list despite never

having been banned. Frequently it is claimed that the War Department

banned the title from military libraries during World War I along with numerous

other "disturbing" and "pacifist" books. Although the

War Department did bar about thirty titles from camp libraries contained in a

list known as the Army "Index," those

books were all pro-German

or anarchist publications. Interestingly, the number of books

banned by

the War Department was far smaller than the number of titles that

librarians

around the country removed from shelves on their own without any

directive or suggestion from any government activitiy. Although

the

American Library Association (ALA) had proclaimed neutrality before the

United

States entered World War I in 1917, the organization and its members,

in fact,

showed a decided anti-German bias. When President Wilson finally

brought

the United States into the conflict, the ALA eagerly and aggressively

supported

his war effort, and librarians from throughout the country purged their

libraries of pro-German works and works by German authors. Typical was

Mr. Edwin

H. Anderson, the director of the New York Public Library, who stated

that

"If Satan wrote a pro-German book we should want it for our reference

shelves. It might be of use to future historians. But in

the circulating department we exclude all pro-German books, and have

done so since the beginning of the war. We go over the books from time to

time and take out those that are objectionable."

|

|

|

|

Ulysses.

James Joyce

began writing his modernist classic, Ulysses,

in 1914 and beginning in 1918, it was serialized in the American

journal, The Little

Review.

The following year its serialization began in the English journal, The Egoist.

While Joyce's

seemingly disjointed combination of streams of consciousness, puns,

jokes, and satire, may have been regarded as bizarre, it wasn't

until 1920, when a chapter describing Leopold Bloom (the main

character) masturbating while fixating upon the legs of a woman, that

it ran

afoul of a group of moralistic busybodies known as the New

York Society for the Suppression of Vice, which took legal action to

keep the

book out of the United States. The ongoing story was declared obscene

in

a trial the following year, and further publication was

prohibited. The United Kingdom followed suit, and the novel

was

also blacklisted by Irish customs. Ulysses remained

banned in the

United States until 1933.

|

|

|

We. In

1921,

Yevgeny

Zamyatin published his classic dystopian novel, We, which

chronicled the oppressive

nature of of a futuristic Marxist totalitarian society organized upon

basic mathematical principles, where people moved and thought in

lockstep and sexual contact was strictly regulated. It was

immediately banned in the Soviet Union. |

|

|

The Bible and The Koran.

From 1926

until 1956, the publication and importation of both the Bible

and the Koran

were prohibited

in the Soviet Union.

|

|

|

The Well of Loneliness.

Radclyffe

Hall published the first lesbian novel, The Well of Loneliness,

in

1928. Knowing that the subject matter was potentially

explosive,

Hall submitted her manuscript to numerous publishers. Its

reception was generally mixed with many editors finding its mediocre

style

and writing more of a drawback than its subject matter. One

publisher, Jonathan Cape, agree to publish the book, and the first

three weeks it was on the market were uneventful. Then, James

Douglas, the editor of the British tabloid newspaper, The Daily

Express, discovered the book. Douglas was

fanatical

moralist and

launched a poster, billboard, and newspaper campaign to have the book

banned. He called on the publisher to withdraw the book and

asked

the Home Secretary to ban it. Jonathon Cape immediately

contacted

the Home Secretary, William Joynson-Hicks, sent him a copy, and

requested his opinion. Within two days, Cape had an

answer.

The Home Secretary found that the book was "gravely detrimental to the

public interest" and threatened the publisher with criminal charges if

it did not immediately withdraw the book. Cape agreed but

attempted to publish the book through a French subsidiary and then

import it back into England. The printings were intercepted

and

confiscated and an obscenity trial ensued. In the end, the

court

determined that the book was, indeed, obscene and that all copies were

to be destroyed. The book was never banned in the United

States. |

|

|

Call of the Wild.

In 1929,

the fascist government of

Italy banned Jack London's Call

of

the Wild, without providing any rationale.

Unlike other of

London's works, the book is without any political content or

point-of-view, so it has been suggested that the banning was simply

because of London's Marxist reputation.

|

|

|

A Farewell to Arms.

In 1929,

Italy also banned Ernest Hemingway's A

Farewell to Arms for its vivid description of the Italian

Army's

disgraceful retreat following the Battle of Caporetto during World War

I.

|

|

|

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes.

The Soviet

Union banned Arthur Conan Doyle's The

Adventures of Sherlock Holmes in 1929 "for

occultism." As

there

are no occult themes in any of the collected stories, it is likely that

the Soviet Union was referring to Doyle's personal belief in the

occult--Doyle also believed in fairies--rather than any specific part

of the book.

|

|

|

Alice in Wonderland.

Numerous

banned book websites report that Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland (Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

and Through the Looking

Glass and

What Alice Found There) was banned in China's Hunan

province in

1931, because "animals should not use human language" and it "put

animals and human beings on the same level." It appears that

this

is actually true, and the books were banned by the provincial governor.

|

|

|

All Quiet on the Western Front.

On 10 May 1933, the newly

elected Nazi Party staged a massive burning of un-German books--i.e.,

books written overwhelmingly, but not exclusively by Jewish

authors--that

had been

stripped from libraries and stores throughout Berlin. Similar

burnings followed in other cities throughout the Germany. The

first

list of specific authors and works to be banned and/or burned

throughout the Reich

was included in an article titled, "Principles for the

Cleansing of

Public Libraries," published a week later in Germany's

leading

library journal.

One of

the few non-Jewish authors whose works were banned primarily

for their anti-war points-of-view was Erich Maria Remarque, however at

the time, Nazi propaganda claimed he was of French Jewish

descent.

|

|

|

The Storm of Steel.

Ernst

Junger served in the German Army during World War One, and in 1918, he

became the youngest man ever to be awarded the Blue Max.

Following the war, he published a candid and brutally honest memoir

describing war in the trenches, however it was widely criticized by

pacifists for its rather neutral point-of-view and Junger's claim that

warfare, "for all its destructiveness, was an incomparable schooling of

the heart." The book was also condemned by the Nazi Party,

and

Junger was prohibited from publishing any new printings after

1934. The Nazis viewed Junger--an ardent nationalist--as a

threat, for although he had little use for democratic institutions, he

thought even less of socialism, especially the brand of socialism

practiced by the Nazis. Despite his dislike for the Nazis,

Junger

served again as an officer during World War Two. He was

implicated as a fringe participant in the von Stauffenberg plot to

assassinate Hitler, but somehow Junger avoided execution.

Following the war, the occupying British forces continued the Nazi's

ban of Junger's works.

|

|

|

The Grapes of Wrath.

In 1939,

John Steinbeck published his classic novel, Grapes

of Wrath, that portrayed the plight of "Okies" who had been displaced

by drought from their farms in Oklahoma and struggled to survive as

migrant farm workers in Kern County, California. Immediately

following its publication, the book came under attack by the Associated

Farmers of California who branded Steinbeck's portrayal of native

Californians' treatment of the Okies as a "pack of lies." The

group found considerable support within the offended population of Kern

County, and the county's board of supervisors officially banned the

book. The ban remained in place for eighteen months until it

was

removed in January of 1941.

|

|

|

The Naked and the Dead.

When

the

25-year-old combat veteran and Harvard graduate, Norman Mailer,

published his classic World War Two novel, The Naked and the Dead, in

1949, it was an immediate best seller. Although Mailer

substituted the word "fug" for "fuck," his otherwise true-to-life use

of soldiers' vernacular still offended many readers, and some critics

called for the book to be banned. Despite the outcry, the

book

was not banned in the United States or in the United Kingdom.

It

was, however, banned for its language in Canada and Australia.

|

|

|

Censorship

Publications Board of Ireland. On 18

December 1953, the Censorship of Publications Board of Ireland banned

almost 100 publications on the grounds that they were indecent or

obscene. Included in this list were Anatole France's Mummer's Tale, All

of John

Steinbeck's work,

Hemingway's The Sun

Also Rises

and Across the River

and into the

Trees, all

of Emile Zola works, C.S. Forester's African

Queen, and almost everything written by William

Faulkner.

Ireland was once described as "the fiercest censorship this side of the

Iron Curtain." Even though Ireland has somewhat lightened

it's

application of internal censorship laws, it remains right at the top of

the censor list.

|

|

|

Doctor

Zhivago. Boris Pasternak was the son of

prominent Russain

Jewish artists; his father, a painter and mother, a concert

pianist. His modernist poetry recieved acclaim within Russia

and

abroad. Unlike many of his friends, Pasternak was excited

about

prospects for Russia following the Bolshevik Revolution, and he

adjusted his style--to the dismay of critics--and began to write poetry

to appeal to the proletariat. Following the Stalinist purges

of

the 1930s, Pasternak became critical of the Communists although his

love for Russia never diminished. Before he ever finished Doctor Zhivago, a

philosophical

love story set in middle of the Russian Revolution, he knew that it

would be banned by Soviet authorities and made arrangements to have it

smuggled into Italy for printing. Upon publication, the book

became

an international best-seller. Of course it was banned in

Russia,

and many in the Communist Party called for Pasternak's imprisonment or

exile. When Pasternak was subsequently awarded the Nobel

Prize

for Literature, he declined the award because he felt that if he left

Russia to receive it, he would not be allowed to return. Doctor Zhivago was

not allowed to

be sold or read in Russia until 1987.

|

|

|

Lady

Chatterley's Lover. D.H. Lawrence finished his

novel, Lady

Chatterley's Lover, a story of

a married but sexually frustrated aristocratic woman who finds physical

satisfaction with the gamekeeper of her husband's estate, in

1920. Its subject matter and, more importantly, frequent use

of

the word "fuck" prevented its publication in England, so Lawrence had

it privately printed in Italy. In 1960, Penguin Books,

published

the book in the United Kingdom as a test of the newly passed obscenity

law that permitted publication of otherwise obscene works it could be

demonstrated that they were of "literary merit." The court

determined that the book had enough literary merit to be

published. A similar trial and appeal in the United States in

1959 had similar results.

|

|

|

Decent Interval.

In 1977,

Frank Snepp, an intelligence analyst who had spent over five years in

Saigon, published a critical examination of what he considered to be

CIA blunders and mismanagement following the Paris Peace Accords of

1973 between North and South Vietnam. Between 1973 and 1975,

Snepp had rightly and repeatedly forecast to his supervisors the

horrendous affect that those one-sided accords and the subsequent U.S.

abandonment of South Vietnam for domestic political reasons would have

upon the region, especially the population of South Vietnam.

When

the tumultuous end came in April of 1979, Snepp's common-law Vietnamese

wife committed suicide and killed their child rather than run the risk

not being able to escape . Snepp, who was evacuated, wrote

his

memoir partly in an attempt to ease the pain of his loss, but also to

demonstrate the impact of the loss of U.S. resolve. After the

unclassified book was published, Snepp was fired from his job and sued

for violation of his "non-disclosure" employment agreement with the CIA

that precluded the publication of any CIA information without the

agency's formal approval. Snepp's case was eventually decided

by

the U.S. Supreme Court, and he lost on all counts. Snepp was

required to give all past and future profit from the book to the U.S.

Treasury and ordered to never again write anything--fact or

fiction--related to his professional past without first submitting the

materials to the CIA for review.

|

|

|

Katherine the Great.

In 1979,

Deborah Davis, published a scathing and partially untrue biography of

Katherine Graham, the legendary "establishment leftist" publisher of

the Washington Post. Among other things, Davis accused Graham

of

being a stooge for the CIA in a supposed attempt to control the free

press. Graham, in turn used her immense power within

publishing

circles to have all 20,000 copies of Davis's book removed from store

shelves and turned into pulp. Davis fought back in a

successful

lawsuit, and the book was re-released to critical scorn in 1991.

|

|

|

Peter Rabbit.

After "Red Ken"

Livingstone's Marxist Labour Party took control of the Greater London

Council in 1981, one of leftist regime's first acts was to ban Beatrix

Potter's Peter Rabbit stories from the city. The Council had

determined that the rabbits and other animals were too middle class and

did not adequately represent the proletariat.

|

|

|

Did Six Million Really Die?

Several countries-- including Austria, Canada, France, and

Germany--have not

just banned but actually criminalized the publication of books that

governmental authorities judge to demean minority groups.

During

the 1980s, Canada twice indicted and convicted Ernst Zundel for

publishing a 1974 book by Richard Harwood, Did Six Million Really Die?

that

challenged the generally accepted extent of the Jewish Holocaust by the

Nazis.

|

|

|

Spycatcher.

In 1985, Peter

Wright, a former British secret agent in MI5, wrote a tell-all memoir

about his experiences with the agency. At the time, Wright

was

terribly embittered by the agency, having lost an appeal to have his

pension payments increased. The United Kingdom immediately

banned

the book, but Wright was successful in having the work published in

Australia despite British attempts to suppress the book there as

well. In 1988, the Law Lords allowed Spycatcher to be

published in the

United Kingdom ruling that the classified materials it contained had

already been compromised when the book was published in Australia.

|

|

|

Little Black Sambo.

The

children's tale, Little

Black Sambo,

is often portrayed as an inherently racist attack on African-

Americans. Actually, it was written in 1899 by Helen

Bannerman,

an Scotswoman living in India and has absolutely nothing to do with

Africans or Americans. The book was incredibly popular

world-wide

for many years but fell into disfavor and began to disappear from store

shelves in the United States with the rise of political

correctness. Although it was frequently challenged and often

removed from libraries on a local basis, it was never legally banned in

the United States. That said, in 1988, the Washington Post

newspaper began a

campaign to have the book banned in Japan, where it's popularity had

never waned. The Post

criticism of Japan spawned a massive letter writing campaign by an

organization, The Association to Stop Racism--which turned out actually

be only a few people--and ignited protests at the Japanese Embassy and

political threats to boycott Japanese cultural exports. The

campaign was successful and all copies of Little Black Sambo

were withdrawn

from sale in Japan in 1988. The title did not reappear for

sale

in Japan until 2005.

|

|

|

The Satanic Verses.

Salman

Rushdie published The

Satanic Verses,

a fictionalized account of the life of Muhammad in 1988 to critical

acclaim throughout the world, except in Muslim nations where parts of

the text were branded by many as blasphemous. Not only was

the

book banned, but in 1989, the Ayatollah Khomeini, the Supreme Leader of

Iran, issued a fatwa announcing, "I inform the proud Muslim people of

the world that the author of The

Satanic Verses book, which is against Islam, the Prophet,

and

the Qur'an, and all those involved in its publication who are aware of

its contents are sentenced to death." Subsequently, Muslims

assassinated the Japanese translator of the book, seriously injured the

Italian translator of the book, and almost killed the Norwegian

publisher of the book. Salman Rusdie remains in hiding, and

when

he appears in person, it is only with extensive personal

security. In 2006, Iran announced the fatwa will remain in

place permanently.

|

|

To the 1800s

To the 2000s

|

|